I recently learned that Comics NOW! magazine has ceased publication. While this did not suprise me a great deal as I know how difficult it is for a new publication to develop a strong readership, I was still saddened by the news. Bryan and the rest of the comic book podcasters worked hard to make this magazine a success. Despite its premature end, it was a quality product that I was proud to be a part of.

While only three Comics Then columns saw print, I had written columns four and five and submitted them to the magazine for publication. As they will not see print in that format, I thought I would share them here on the Golden Age blog. So, without further ado, here is Comics Then #4.

“The Beginning of the End or a New Beginning?”

The year was 1954. Television was taking over American homes and the United States was in the midst of the Cold War. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s most infamous anti-communism hearings (The “Army-Communism” hearings) were televised and ultimately led to his downfall and censure by the United States Senate. At the same time, television and the United States Senate dealt a similar blow to the comic book industry.

In April and June of 1954, Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver, a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, held hearings on juvenile delinquency in the United States and focused on crime and horror comics. Of course, this fire had been fueled by the anti-comic book crusade of Fredric Wertham, that culminated in his now infamous book, The Seduction of the Innocent and similar hearings in the State of New York, but it was the events of the Senate Hearings that brought the most scrutiny to the world of comic book publishing in 1954. It was a different world from the early days of the Golden Age. The superheroes had all but fled the scene, leaving the spinner racks to be dominated by the crime and horror comics that first appeared in the late 1940’s. The effect of television also contributed to this “perfect storm”, as comic book readership had declined in part due to the new entertainment medium, and comics publishers were scrambling to find new content to bring in new audiences. They found that sex, violence, and gore did the trick (This kind of sounds like the debate we hear about modern entertainment, doesn’t it?)

The beginning of the end came on April 21, 1954, when William “Bill” Gaines of Entertaining Comics appeared to testify before the Committee. Gaines, whose “EC” line included Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, Crime SuspenStories, Shock SuspenStories, and others, had taken crime and horror comics to new levels of gore and violence, and had attracted the attention of the Senate Committee. Today, we all know that Gaines had employed some of the most talented artists and writers in comics to craft his now classic stories, but all of that was lost to the Committee, whose mission was to root out the cause of juvenile delinquency in the United States. Gaines’ testimony made their job easy.

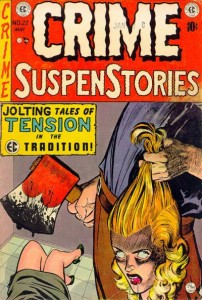

In his opening remarks, he extolled the virtue of his publications, and argued that they were entertaining and good for children to read (including reminding the Committee that he published Picture Stories from the Bible). That all sounded great until Gaines was confronted with his cover from Crime SuspenStories #22 (April-May 1954). The cover depicted a man holding a bloody ax in one hand and a woman’s severed head (complete with eyes rolled back and blood oozing from the corners of her mouth) in the other. The following exchange in many ways spelled the end of the crime and horror comics of the day:

Mr. Beasor (Herbert Wilton Beasor, Chief Counsel to the Committee): There would be no limit actually to what you put in the magazines?

Mr. Gaines: Only within the bounds of good taste.

Mr. Beasor: Your own good taste and salability?

Mr. Gaines: Yes.

Senator Kefauver: Here is your May 22 issue. This seems to be a man with a bloody ax holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

Mr. Gaines: Yes, sir; I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

Senator Kefauver: You have blood coming out of her mouth.

Mr. Gaines: A little.

Senator Kefauver: Here is blood on the ax. I think most adults are shocked by that.

The Chairman (Robert C. Hendrickson, New Jersey): Here is another one I want to show him.

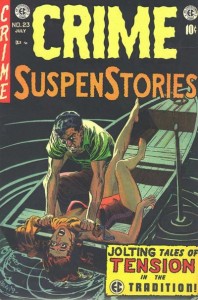

Senator Kefauver: This is the July one (CrimeSuspenStories #23, June-July 1954). It seems to be a man with a woman in a boat and he is choking her to death here with a crowbar. Is that good taste?

Mr. Gaines: I think so.

As the old saying goes, a picture speaks a thousand words, and Gaines’ attempt at an eloquent rebuttal fell on deaf ears. Needless to say, the comic book publishers saw governmental censorship on the horizon and decided to take matters into their own hands. The result was the creation by the industry of the Comics Code Authority, whose rules the publishers willingly agreed to follow. Publishers of crime and horror comics like Gaines’ EC had no choice but to capitulate or be put out of business. Many chose to close their doors, and Gaines’ attempt at his “New Direction” line of code- approved comics did not last long. It was only Gaines’ bold move of converting one of his humor comics into a magazine to avoid the Comics Code that saved EC. That comic was Mad, and the rest was history as Mad magazine went on to be one of the most successful humor publications of all time.

But what about the rest of the industry? Well, the post-Comics Code Authority world was really a new beginning as it signaled the definite end of the Golden Age of Comic Books and the birth of the Silver Age of Comics with Showcase #4, and the introduction of the Silver Age Flash. The superheroes were back!

Whether you agree with the arguments of Wertham and the crusade of Estes Kefauver, the events of 1954 were a watershed moment in the history of comic books, and set the stage for the success of the medium we enjoy today.

2 Responses to Comics Then #4 – The Beginning of the End or a New Beginning?