In entering these orders, Judge Larson made detailed factual findings worthy of any fanzine in his description of the history behind the creation of Superman and the subsequent turmoil that ensued between DC and Siegel & Shuster. Once again, instead of paraphrasing this historical review , I am reprinting it here (sans most of the legal citations) for the sake of completion:

Any discussion about the termination of the initial grant to the copyright in a work begins, as the Court does here, with the story of the creation of the work itself.

In 1932, Jerome Siegel and Joseph Shuster were teenagers at Glenville High School in Cleveland, Ohio. Siegel was an aspiring writer and Shuster an aspiring artist; what Siegel later did with his typewriter and Shuster with his pen would transform the comic book industry. The two met while working on their high school’s newspaper where they discovered their shared passion for science fiction and comics, the beginning of a remarkable and fruitful relationship.

One of their first collaborations was publishing a mail-order fanzine titled “Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization.” In the January, 1933, issue, Siegel and Shuster’s first superman character appeared in the short story “The Reign of the Superman,” but in the form of a villain not a hero. The story told of a “mad scientist’s experiment with a deprived man from the breadlines” that transformed “the man into a mental giant who then uses his new powers-the ability to read and control minds-to steal a fortune and attempt to dominate the world.” This initial superman character in villain trappings was drawn by Shuster as a bald-headed mad man.

A couple of months later it occurred to Siegel that re-writing the character as a hero, bearing little resemblance to his villainous namesake, “might make a great comic strip character.” Much of Siegel’s desire to shift the role of his protagonist from villain to hero arose from Siegel’s exposure to despair and hope: Despair created by the dark days of the Depression and hope through exposure to the “gallant, crusading heros” in popular literature and the movies. The theme of hope amidst despair struck the young Siegel as an apt subject for his comic strip: “Superman was the answer-Superman aiding the downtrodden and oppressed.”

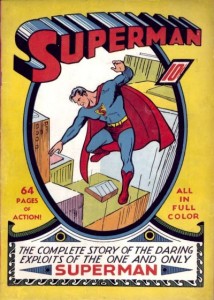

Thereafter, Siegel sat down to create a comic book version of his new character. While he labored over the script, Shuster began the task of drawing the panels visualizing that script. Titling it “The Superman,” “[t]heir first rendition of the man of steel was a hulking strongman who wore a T-shirt and pants rather than a cape and tights.” And he was not yet able to hurdle skyscrapers, nor was he from a far away planet; instead, he was simply a strong (but not extraordinarily so) human, in the mold of Flash Gordon or Tarzan, who combated crime. Siegel and Shuster sent their material to a publisher of comic books-Detective Dan-and were informed that it had been accepted for publication. Their success, however, was short-lived; the publisher later rescinded its offer to publish their submission. Crestfallen, Shuster threw into the fireplace all the art for the story except the cover (reproduced below), which Siegel rescued from the flames.

Undaunted, Siegel continued to tinker with his character, but decided to try a different publication format, a newspaper comic strip. The choice of crafting the material in a newspaper comic strip format was influenced both by the failure to get their earlier incarnation of the Superman character published by Detective Dan in a comic book format, and by the fact that, at the time, black-and-white newspaper comic strips-not comic books-were the most popular medium for comics. As one observer of the period has commented:

It is worth noting the extent to which early comic books were conjoined with newspaper strips of the day. The earliest comic books consisted of reprints of those newspaper strips, re-pasted into a comic book page format. When original material began appearing in comic book format, it was generally because companies that wished to publish comic books were unable to procure reprint rights to existing newspaper strips. The solution to this … was to hire young [comic strip artists] to simulate the same kind of newspaper strip material.

On a hot summer night in 1934, Siegel, unable to sleep, began brainstorming over plot ideas for this new feature when an idea struck him: “I was up late counting sheep and more and more ideas kept coming to me, and I wrote out several weeks of syndicate script for the proposed newspaper strip. When morning came, I dashed over to Joe [Shuster]’s place and showed it to him.” Siegel re-envisioned his character in more of the mythic hero tradition of Hercules, righting wrongs in present-day society. His inspiration was to couple an exaggeration of the daring on-screen acrobatics performed by such actors as Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., with a pseudo-scientific explanation to make such fantastic abilities more plausible in the vein of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars stories, and placing all of this within a storyline that was the reverse of the formula used in the Flash Gordon serials. The end product was of a character who is sent as an infant to Earth aboard a space ship from an unnamed distant planet (that had been destroyed by old age) who, upon becoming an adult, uses his superhuman powers (gained from the fact that his alien heritage made him millions of years more evolved than ordinary humans) to perform daring feats for the public good.

Siegel named his character “Superman.” Unlike his previous incarnation, Siegel’s new Superman character’s powers and abilities were much more extraordinary and fantastic: Superhuman strength; the ability to leap 1/8th of a mile, hurdle a twenty-story building, and run faster than an express train; and nothing less than a bursting shell could penetrate his skin. Siegel placed his character in a very cosmopolitan environment that had the look and feel of mid-thirties America. He also humanized his character by giving his superhero an “ordinary person” alter ego: Mild-mannered, big-city newspaper reporter Clark Kent. Siegel developed this concept of Superman’s secret identity both as a means for his superhero to maintain an inconspicuous position in everyday society and as a literary device to introduce a conflict-and the potential for story lines centered around that conflict-between the character’s dual identities, a conflict played out no more dramatically than in the love “triangle” between the character’s dual identities and another newspaper reporter, Lois Lane.

Shuster immediately turned his attention to giving life and color to Siegel’s idea by drawing illustrations for the story. Shuster conceived of the costume for Siegel’s Superman superhero-a cape and tight-fitting leotard with briefs, an “S” emblazoned on an inverted triangular crest on his chest, and boots as footwear. In contrast, he costumed Clark Kent in a nondescript suit, wearing black-rimmed glasses, combed black hair, and sporting a fedora. He drew Superman and his alter ego Clark Kent with chiseled features, gave him a hairstyle with a distinctive curl over his forehead, and endowed him with a lean, muscular physique. Clark Kent hid most of these physical attributes behind his wardrobe, which he could quickly doff revealing his Superman costume underneath when he was called to action by someone in need of his superpowers. One of the earliest of Shuster’s sketches of Superman and Clark Kent from this 1934 or 1935 period are depicted below:

The two then set about combining Siegel’s literary material with Shuster’s graphical representations. Together they crafted a comic strip consisting of several weeks’ worth of material suitable for newspaper syndication. Siegel typed the dialogue and Shuster penciled in artwork, resulting in four weeks of Superman comic strips intended for newspapers. The art work for the first week’s worth “of daily [comic] strips was completely inked” and thus ready for publication. The “three additional weeks of ‘Superman’ newspaper comic strip material” differed from the first week’s material “only in that the art work, dialogue and the balloons in which the dialogue appeared had not been inked,” instead consisting of no more than black-and-white pencil drawings.

Siegel also wrote material to which Shuster provided no illustrations: A paragraph previewing future Superman exploits, and a nine-page synopsis of the storyline appearing in the three weeks of penciled daily Superman newspaper comic strips.

The two shopped the character for a number of years to numerous publishers but were unsuccessful. As Siegel later recalled: One publisher “expressed interest in Superman,” but preferred that it be “published in comic book form where it would be seen in color” rather than “a black-and-white daily strip,” a suggestion to which he and Shuster balked given their earlier experience with the comic book publisher of Detective Dan.

In the meantime, Siegel and Shuster penned other comic strips, most notably “Slam Bradley” and “The Spy,” that were sold to Nicholson Publishing Company. When Nicholson folded shop in 1937, Detective Comics acquired some of its comic strip properties, including “Slam Bradley” and “The Spy.”

On December 4, 1937, Siegel and Shuster entered into an agreement with Detective Comics whereby they agreed to furnish some of these existing comic strips for the next two years, and further agreed “that all of these products and work done by [them] for [Detective Comics] during said period of employment shall be and become the sole and exclusive property of [Detective Comics,] and [that Detective Comics] shall be deemed the sole creator thereof ….” The agreement further provided that any new or additional features by Siegel and Shuster were to be submitted first to Detective Comics, who was given a sixty-day option to publish the material.

Soon thereafter Detective Comics decided to issue a new comic book magazine titled Action Comics and began seeking new material. Inquiry was made of many newspaper comic strip publishers, including McClure Newspaper Syndicate. Amongst the material submitted by McClure to Detective Comics was the previously rejected Siegel and Shuster Superman comic strip. Detective Comics soon became interested in publishing Siegel and Shuster’s now well-traveled Superman material, but in an expanded thirteen-page comic book format, for release in its first volume of Action Comics.

On February 1, 1938, Detective Comics returned the existing Superman newspaper comic strip material to Siegel and Shuster for revision and expansion into a full-length, thirteen-page comic book production. Detective Comics’ desire to place Superman in a comic book required that Siegel and Shuster reformat their existing Superman newspaper material by re-cutting the strip into separate panels and then re-pasting it into a comic book format.

An issue emerged due to Detective Comics’ additional requirement that there be eight panels per page in the comic book. Siegel and Shuster’s existing Superman newspaper material did not have enough drawings to meet this format. In response, portions of the thirteen-page comic went forward with fewer than eight panels per page, and in the remaining pages Shuster either trimmed or split existing panels to stay within the page size, or drew additional panels from the existing dialogue to meet the eight-panel requirement. As Shuster later recounted:

The only thing I had to do to prepare Superman for comic book publication was to ink the last three weeks of daily strips which I had previously completely penciled in detail. In addition, I inked the lettering and the dialogue and story continuity and inked in the balloons containing the dialogue. Certain panels I trimmed to conform to Detective’s page size. I drew several additional pictures to illustrate the story continuity and these appear on page 1 of the first Superman release. This was done so that we would be certain of having a sufficient number of panels to make a thirteen page release. Finally, I drew the last panel appearing on the thirteenth page. Detective’s only concern was that there would be panels sufficient for thirteen complete pages. Jerry told me that Detective preferred having eight panels per page but in our judgment this would hurt the property. I specifically refer to the very large panel appearing on what would be page 9 of the thirteen page release. We did not want to alter this because of its dramatic effect. Accordingly, on this page but six panels appeared.

Siegel similarly recollected:

Upon receiving word from Detective that we could proceed, Joe Shuster, under my supervision, inked the illustrations, lettering and dialogue balloons in the three weeks of daily strips that had been previously penciled. In addition, he trimmed certain pictures to meet Detective’s panel specifications and extended others. To assure ourselves of having the proper number of panels we added several pictures to illustrate the story continuity, I had already written. Added as well for this reason was the scientific explanation on page 1 of the release and the last panel at the foot of page 13.

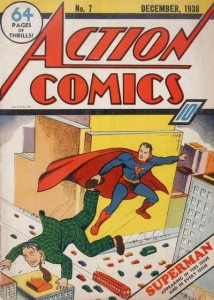

On or around February 16, 1938, the pair resubmitted the re-formatted Superman material to Detective Comics. Soon thereafter Detective Comics informed Siegel that, as he had earlier suggested to them, one of the panels from their Superman comic would be used as the template (albeit slightly altered from the original) for the cover of the inaugural issue of Action Comics.

On March 1, 1938, prior to the printing of the first issue of Action Comics, Detective Comics wrote to Siegel, enclosing a check in the sum of $130, representing the per-page rate for the thirteen-page Superman comic book release and enclosing with it a written agreement for Siegel and Shuster’s signatures. The agreement assigned to Detective Comics “all [the] good will attached … and exclusive right[s]” to Superman “to have and hold forever.” Siegel and Shuster executed and returned the written assignment to Detective Comics.

This world-wide grant in ownership rights was later confirmed in a September 22, 1938, employment agreement in which Siegel and Shuster acknowledged that Detective Comics was “the exclusive owner[ ]” of not only the other comic strips they had penned for Nicholson (and continued to pen for Detective Comics), but Superman as well; that they would continue to supply the artwork and storyline (or in the parlance of the trade, the “continuity”) for these comics at varying per-page rates depending upon the comic in question for the next five years; that Detective Comics had the “right to reasonably supervise the editorial matter” of those existing comic strips; that Siegel and Shuster would not furnish “any art copy … containing the … characters or continuity thereof or in any wise similar” to these comics to a third party; and that Detective Comics would have the right of first refusal (to be exercised within a six-week period after the comic’s submission) with respect to any future comic creations by Siegel or Shuster.

Detective Comics announced the debut of its Action Comics series with full page announcements in the issues of some of its existing publications. Specifically, in More Fun Comics, Vol. 31, with a cover date of May, 1938, Detective Comics placed the following black-and-white promotional advertisement on the comic’s inside cover, which reproduced the cover of the soon-to-be published first issue of Action Comics, albeit in a greatly reduced size:

Similarly, Detective Comics, Vol. 15, with a cover date of May, 1938, had a full-page black-and-white promotional advertisement on the comic’s inside cover which contained within it a reproduction of the cover (again in a reduced scale) of the soon-to-be published first issue of Action Comics:

To provide some context and contrast, the cover of the first issue of Action Comics is notable for its difference from the promotional advertisements both in its scale and its colorized format.

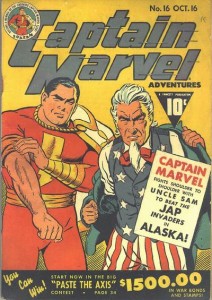

Superman itself was published by Detective Comics on April 18, 1938, in Action Comics, Vol. 1, which had a cover date of June, 1938. A full reproduction of the original Superman comic contained in Action Comics, Vol. 1, is attached as an addendum to this Order. See Attachment A to this Order. The Superman comic became an instant success, and Superman’s popularity continues to endure to this day as his depiction has been transferred to varying media formats.

The Superman character has evolved in subsequent works since his initial depiction in Action Comics, Vol. 1. These additional works have added decades of new material to further define, update, and develop the character (such as his origins, his relationships, and his powers and weaknesses) in an ongoing flow of new exploits and supporting characters, resulting in the creation of an entire fictional Superman “universe.” For instance, absent from Action Comics, Vol. 1, was any reference to some of the more famous story elements now associated with Superman, such as the name of Superman’s home planet “Krypton.” Many of Superman’s powers that are among his most famous today did not appear in Action Comics, Vol. 1, including his ability to fly (even through the vacuum of space); his super-vision, which enables him to see through walls (“x-ray” vision) and across great distances (“telescopic” vision); his super-hearing, which enables him to hear conversations at great distances; and his “heat vision,” the ability to aim rays of extreme heat with his eyes. The “scientific” explanation for these powers was also altered in ensuing comics, initially as owing to differences in gravity between Earth and Superman’s home planet (the latter being much larger in size than the former), and later because Krypton orbited a red sun, and his exposure to the yellow rays of Earth’s sun somehow made his powers possible. In a similar Earth-Krypton connection, it was later revealed that Superman’s powers could be nullified by his exposure to Kryptonite, radioactive mineral particles of his destroyed home planet.

Aside from the further delineation of Superman’s powers and weaknesses, many other elements from the Superman story were developed in subsequent publications. Some of the most famous supporting characters associated with Superman, such as Jimmy Olsen and rival villains Lex Luthor, General Zod, and Brainiac, were created long after Action Comics, Vol. 1, was published. Moreover, certain elements contained in Action Comics, Vol. 1, were altered, even if slightly, in later publications, most notably Superman’s crest. In Action Comics, Vol. 1, the crest emblem was a small, yellow, inverted triangle bearing the letter “S” in the middle, shown throughout the comic as solid yellow in most instances and as a red “S” in two instances. Thereafter, the emblem changed, and today is a large yellow five-sided shield, outlined in the color red, and bearing the letter “S” in the middle, also in the color red.

The acclaim to which the release of Action Comics, Vol. 1, was greeted by the viewing public quickly made Superman not only the iconic face for the comic book industry but also a powerful super-salesman for his publisher. Detective Comics oversaw the creation, development, and licensing of the Superman character in a variety of media, including but not limited to radio, novels, live action and animated motion pictures, television, live theatrical productions, merchandise and theme parks. From such promotional activity, Detective Comics came to “own[ ] dozens of federal trademark registrations for Superman related indicia, such as certain key symbols across a broad array of goods and services.” The most notable of these marks that are placed on various items of merchandise are “Superman’s characteristic outfit, comprised of a full length blue leotard with red cape, a yellow belt, the S in Shield Device, as well as certain key identifying phrases [,]” such as “ ‘Look! … Up in the sky! … It’s a bird! … It’s a plane! … It’s Superman!”

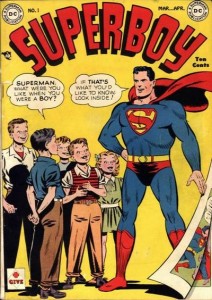

Meanwhile, Siegel continued to submit other comic book characters to Detective Comics that were also published. Sometimes these submissions were without Shuster serving as an illustrator and sometimes, such as in the case of Superman’s youthful persona “Superboy,” see Siegel v. Time Warner Inc., 496 F.Supp.2d 1111 (C.D.Cal.2007), without illustrations accompanying the submission. Among these subsequent creations was “The Spectre,” a comic written by Siegel and illustrated by Bernard Baily, which first appeared in 1940 in Detective Comics’ More Fun Comics, Vol. 52. The comic told the story about a superhero with a supernatural bent-the character being the spirit of a police officer killed in the line of duty while investigating a gangland overlord and who, after meeting a higher force in the hereafter, is sent back to Earth with nearly limitless abilities but offered eternal rest only when he has wiped out all crime.

With Superman’s growing popularity, a growing rift developed between the parties. Siegel and Shuster believed that Detective Comics poached the artists apprenticing out of Siegel and Shuster’s studio in Cleveland by moving them in-house to its New York offices, and further believed that Detective Comics had not paid them their fair share of profits generated from the exploitation of their Superman creation and from the profits generated from copycat characters that they believed had their roots in the original Superman character. As a result, in 1947, Siegel and Shuster brought an action against Detective Comics’ successor in interest in New York Supreme Court, Westchester County, seeking, among other things, to annul and rescind their previous agreements with Detective Comics assigning their ownership rights in Superman as void for lack of mutuality and consideration.

After a trial, official referee J. Addison Young issued detailed findings of fact and conclusions of law wherein he found that the March 1, 1938, assignment of the Superman copyright to Detective Comics was valid and supported by valuable consideration and that, therefore, Detective Comics was the exclusive owner of “all” the rights to Superman. The parties eventually settled the Westchester action and signed a stipulation on May 19, 1948, whereby in exchange for the payment of over $94,000 to Siegel and Shuster, the parties reiterated the referee’s earlier finding that Detective Comics owned all rights to Superman. Two days later, the official referee entered a final consent judgment vacating his earlier findings of fact and conclusions of law, and otherwise reiterating the recitals contained in the stipulation.

The feud between the parties did not end after the Westchester action. In the mid-1960s, the simmering dispute boiled anew when the expiration of the initial copyright term for Superman led to another round of litigation over ownership to the copyright’s renewal term. In 1969, Siegel and Shuster filed suit in federal district court in New York seeking a declaration that they, not Detective Comics’ successor (National Periodical Publications, Inc.), were the owners of the renewal rights to the Superman copyright. See Siegel v. National Periodical Publications, Inc., 364 F.Supp. 1032 (S.D.N.Y.1973), aff’d by, 508 F.2d 909 (2nd Cir.1974). The end result of the litigation was that, in conformity with United States Supreme Court precedent at the time, see Fred Fisher Music Co. v. M. Witmark & Sons, 318 U.S. 643, 656-59, 63 S.Ct. 773, 87 L.Ed. 1055 (1943), in transferring “all their rights” to Superman in the March 1, 1938, grant to Detective Comics (which was reconfirmed in the 1948 stipulation), Siegel and Shuster had assigned not only Superman’s initial copyright term but the renewal term as well, even though those renewal rights had yet to vest when the grant (and later the stipulation) was made.

After the conclusion of the 1970s Superman litigation, the New York Times “ran a story about how the two creators of Superman were living in near destitute conditions”:

Two 61-year-old men, nearly destitute and worried about how they will support themselves in their old age, are invoking the spirit of Superman for help. Joseph Shuster, who sits amidst his threadbare furniture in Queens, and Jerry Siegel, who waits in his cramped apartment in *1113 Los Angeles, share the hope that they each will get pensions from the Man of Steel.

Mary Breasted, Superman’s Creators, Nearly Destitute, Invoke His Spirit, N.Y. Times, Nov. 22, 1975, at 62.

Apparently in response to the bad publicity associated with this and similar articles, the parties thereafter entered into a further agreement, dated December 23, 1975. See id. (“ ‘There is no legal obligation,’ Mr. Emmett [, executive vice-president of Warner Communications, Inc.,] said, ‘but I sure feel that there is a moral obligation on our part’ ”). In the agreement, Siegel and Shuster re-acknowledged the Second Circuit’s decision that “all right, title and interest in” Superman (“including any and all renewals and extensions of … such rights”) resided exclusively with DC Comics and its corporate affiliates and, in return, DC Comics’ now parent company, Warner Communications, Inc. (“WCI”), provided Siegel and Shuster with modest annual payments for the remainder of their lives; provided them medical insurance under the plan for its employees; and credited them as the “creators of Superman.” In tendering this payment, Warner Communications, Inc. specifically stated that it had no legal obligation to do so, but that it did so solely “in consideration” of the pair’s “past services … and in view of [their] present circumstances,” emphasizing that the payments were “voluntary.” The 1975 agreement also made certain provisions for Siegel’s spouse Joanne, providing her with certain monthly payments “for the balance of her life if Siegel” died before December 31, 1985. Finally, Warner Communications, Inc. noted that its obligation to make such voluntary payments would cease if either Siegel or Shuster (or their representatives) sued “asserting any right, title or interest in the ‘Superman’ … copyright.”

As the years went by Warner Communications, Inc. increased the amount of the annual payments, and on at least two occasions paid the pair special bonuses.

As the time grew nearer to the December 31, 1985, cutoff date for surviving spouse benefits, Joanne Siegel wrote the CEO for DC Comics expressing her “terrible worry” over the company’s refusal to provide Jerome Siegel life insurance in the 1975 agreement. She voiced her concern that, should anything happen to her husband after the cutoff date, she and their daughter “would be left without any measure of [financial] security.” The parties thereafter agreed by letter dated March 15, 1982, that Warner would pay Joanne Siegel the same benefits it had been paying her husband if he predeceased her, regardless of the time of his death. Jerome Siegel died on January 28, 1996, and Joanne Siegel has been receiving these voluntary survival spouse benefits since that time.

In the meantime, changes in the law resurrected legal questions as to the ownership rights the parties had to the Superman copyright. With the passage of the Copyright Act of 1976 (the “1976 Act”), Congress changed the legal landscape concerning artists’ transfers of the copyrights in their creations. First, the 1976 Act expanded by nineteen years the duration of the renewal period for works, like the initial release of Superman in Action Comics, Vol. 1, that were already in their renewal term at the time of the Act’s passage. See 17 U.S.C. § 304(b).

Second, and importantly for this case, the 1976 Act gave artists and their heirs the ability to terminate any prior grants of the rights to their creations that were executed before January 1, 1978, regardless of the terms contained in such assignments, e.g., a contractual provision that all the rights (the initial and renewal) belonged exclusively to the publisher. Specifically, section 304(c) to the 1976 Act provides that, “[i]n the case of any copyright subsisting in either its first or renewal term on January 1, 1978, other than a copyright in a work made for hire, the exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer or license of the renewal copyright or any right under it, executed before January 1, 1978, … is subject to termination … notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary ….”

Judge Larson went on to detail the months of near-succesful settlement negotiations between DC and the Siegels, but in the end their differences were too great and suit was filed against DC.

After making his ruling regarding the scope of the reclaimed copyrights by the Siegel family, Judge Larson indicated that the parties would next go forward to have hearings to decide how much, if anything, DC owed to the Siegel family. The process continues…

If you want to read the entirety of Judge Larson’s orders, here are the legal citations: